Clarification and Transposition; New Features for the Module for Transcription of Primary Sources? Some Thoughts after Experiences with the Manuscripts of Henrik Ibsen

(Hilde Bøe, Munch Museum)

Introduction

The project Henrik Ibsen’s

Writings (HIW) aims at diplomatic and detailed encoding in the transcriptions of

Ibsen’s manuscripts. When we began transcribing Ibsen’s manuscripts we soon

encountered challenges trying to represent his changes with the manuscript

encoding of TEI P4, and we would have had more or less the same challenges if we

converted to P5. Clarifications and transpositions are alteration types that are

not covered by the Guidelines and which we found frequently enough to decide to

add our own solutions. Here I will discuss the characteristics of

transpositions, and I will elaborate on the general problem of encoding

alterations genetically. I will also touch on clarifications, which is a less

complex phenomenon.

The project Henrik Ibsen’s

Writings (HIW) aims at diplomatic and detailed encoding in the transcriptions of

Ibsen’s manuscripts. When we began transcribing Ibsen’s manuscripts we soon

encountered challenges trying to represent his changes with the manuscript

encoding of TEI P4, and we would have had more or less the same challenges if we

converted to P5. Clarifications and transpositions are alteration types that are

not covered by the Guidelines and which we found frequently enough to decide to

add our own solutions. Here I will discuss the characteristics of

transpositions, and I will elaborate on the general problem of encoding

alterations genetically. I will also touch on clarifications, which is a less

complex phenomenon.

As a starting point though, I’d like to make a couple of remarks about modern working draft manuscripts (i.e. the writer’s notes and drafts prior to the final manuscript prepared for printing) and premodern manuscripts (e.g. medieval manuscripts). It is possible to differentiate between the alterations in modern and premodern manuscripts in a way that can illustrate matters of interest to us in the discussion of encoding manuscript alterations. Modern working draft manuscripts have a private character; they are usually meant for their writer only. Premodern manuscripts are public and written for an audience. Scribes need to mark alterations more or less in the same way so that they do not disturb reading and are understood by both readers and future scribes. Alterations in a working draft manuscript on the other hand need only to be understood by their creator, the writer. This means that different marks can be used for the same kind of alteration and that there can be several marks for the same phenomenon in the same manuscript or throughout an authorship.

Another characteristic aspect of modern working draft manuscripts versus premodern manuscripts is that the first often represent several stages in a creative process, they really are, using John Bryant’s term (Bryant 2002), fluid texts; while the latter acts as carriers of one text, transmitters of the work 1 . The first reflect stages in the ongoing process of writing, the latter aims at delivering the work unaltered or even in better condition, to new readers. As a consequence, alterations are far more frequent, larger or more complex in working draft manuscripts.

None of this is new, but I believe that these differences are not sufficiently reflected in the available manuscript encoding of the TEI. Summed up, one could say that the challenges in encoding modern manuscripts lay in coping with the many differing revisions they contain and the versions they represent. Capturing all of the alterations in a working draft manuscript therefore require an encoding that allows us to mark up the structures of revision and version. The encoding has to be flexible and differentiated to allow us to mark up not only the many different types of alterations, but also to mark them up as consistently as possible, preferably using the same encoding for all variants of one type of alteration. We lack elements for some types of alterations, and some of the existing elements lack the flexibility we need to be able to represent the genetic process; the structure of revision. I’ll attend to the issue of flexibility later on. First I’ll take a look at the lacking elements.

Clarifications

Henrik Ibsen clarified his writing, repeating the same word or character on top of the unclear word or character, or repeating it somewhere offline. Clarification is not a correction, nor is it an addition in the strict sense of the word, nor is it a substitution, and although it could be encoded as either of these, we believe that that would be stretching the intended use of these elements too far and simultaneously ignoring the writer's intention; making reading easier. HIW has therefore created a new element called <clarification> which encloses the clarified character(s) or word(s); thus we transcribe the text once only although it’s written twice). In addition to the global attributes the element has the @hand attribute. 2

Bæg<clarification place=”inline”>er</clarification>klang

-

- From Brand, Collin 262, 4°, I.1.1. The Royal Library of Copenhagen, Denmark

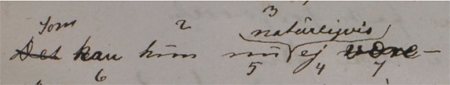

Later we have discovered that the manuscripts also contain what can be perceived as offline clarifications (see the second example, the facsimile from the printer’s copy of The Wild Duck). Probably because he was afraid his correction of “t” to “vt” was too unclear for his printer, he has repeated the characters above the line to make sure the word is readable. We do not encode these as clarifications, only as ordinary additions and overwritten deletions.

(hal<add place=”supralinear”>vt</add>

<del rend=”overwritten”>t</del>

<add place=”inline”>vt</add>

afklædt, i forstuen.)

Today I think we would have created a slightly different <clarification> element, since this last example really isn’t an addition of something new. This “correction” makes sense only if it’s regarded as a clarification. And to encode the repeated characters with <clarification> instead of <add>, puts sense back into the encoding and makes it more consistent. <clarification> could be moulded with the overwritten deletion as a model. This would mean transcribing both the original and the clarified text, and would result in a more diplomatic transcription, especially with regard to the offline clarifications.

Transpositions

With transposition HIW understands textual elements that switch positions with each other. The TEI Guidelines defines it like this: “Another feature commonly encountered in manuscripts is the use of circles, lines, or arrows to indicate transposition of material from one point in the text to another. No specific mark-up for this phenomenon is proposed at this time. Such cases are most simply encoded as additions at the point of insertion and deletions at the point of encirclement or other marking.” 3 When bits of text are moved from one position to another, HIW don’t define them as transposed; only moved.

Transpositions where a rearrangement of a group of textual elements, is marked with numbers, are not mentioned here at all. In Ibsen’s manuscripts numbered transpositions are far more frequent than “the use of circles, lines, or arrows to indicate transposition”, although lines or arrows sometimes accompany the numbers. The moving of text from one location to another is something we’ve encountered far more seldom, and it would be interesting to know more about the frequency of transpositions in other authors’ manuscripts.

Textual elements of nearly all kinds and sizes can be transposed in Ibsen’s manuscripts; words, phrases, (verse) lines and (verse) line blocks. The number of elements to transpose can also vary; we’ve encountered a transposition where six words are marked for rearrangement with numbers. For Ibsen, who was writing verse and working with pen and paper, transposition was a convienient and important way to revise text.

…of phrases and words

Inline we’ve encountered transpositions of phrases and words. Words or phrases that are to be transposed usually appear directly next to each other, but there are examples where there is text in-between the words as well. I have some examples here.

-

- From Poems, Ms.4º 1110a. The National Library of Norway. Here a word appears between the two words marked for transposition.

-

- From The Epic Brand, NKS 2869, 4°, 1. The Royal Library of Copenhagen, Denmark. This transposition includes one phrase and one word, and it’s marked with underlined numbers below the line as well as with a conventional proof¬reading mark for transposing two textual elements.

-

- Also from The Epic Brand, NKS 2869, 4°, 1. The Royal Library of Copenhagen, Denmark. Two phrases are marked for transposition with numbers above and underlining below (hardly visible under the first phrase).

-

- Also from The Epic Brand, NKS 2869, 4°, 1. The Royal Library of Copenhagen, Denmark. The two words are marked with numbers, and the second number includes an overwriting.

-

- From Brand, KBK 262, 4°, I, 1.1. The Royal Library of Copenhagen, Denmark. Four words are marked for transposition.

-

- From Love’s Comedy, UBiT Ms Oct. 375. The University Library of Trondheim, Norway. In this example with five numbered words, the numbers are put below the line.

-

- Also from Love’s Comedy, UBiT Ms Oct. 375. The University Library of Trondheim, Norway. This transposition includes other alterations as well; an added word and two overwritten words are parts of it. Totally six words are numbered for this transposition, some above and some below the line.

…of lines or line blocks

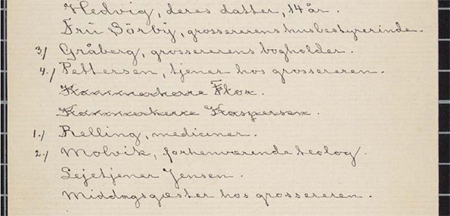

Ibsen also transposes verse lines or groups of verse lines in poems and verse dramas, or he transposes cast items in cast lists. Here are some examples.

-

- From The Wild Duck, Ms.4º 1115a. The National Library of Norway. Two pairs of lines in a cast list are marked for transposition with numbers in the left margin. Since Ibsen doesn’t reverse the order of each line pair, the numbering of each line is somewhat pedantic.

-

- From The Epic Brand, NKS 2869, 4°, 1. The Royal Library of Copenhagen, Denmark. Another example; a transposition of two lines is marked twice, with numbers and a line.

-

- Also from The Epic Brand, NKS 2869, 4°, 1. The Royal Library of Copenhagen, Denmark. In this transposition two pairs of verse lines are braced and numbered to indicate the rearrangement.

I hope these examples from Ibsen’s manuscripts have convinced you of the variety in which transpositions can be shaped.

Regarding encoding 4 , I won’t go into details, just say that I would prefer an interlevel element along the same lines as <stage> since where transpositions can appear and what they can contain vary in much the same way as for stage directions.

Diplomatic transcriptions for genetic editions

The revisions of a text are the main focus in diplomatic transcriptions for genetic editions. The problem for those of us, who have this focus, is that many types of alterations have more variants than the current TEI elements are able to handle. The variety of transpositions emphasises this.

In HIW we use TEI P4’s <app> element (with its’ <lem> and <rdg> elements) in combination with <add> and <del> for the smaller, straightforward substitutions. Although TEI P5 now has the element <subst> for substitutions, the problems are still much the same as they were in TEI P4, as was demonstrated on the TEI MS SIG discussion list in July this year in a discussion entitled “<subst> and genetic editions”. 5 I agree with Elena Pierazzo when she asks if it wouldn’t be better to rethink the <subst> element. From the point of view of establishing genetic editions it’s not satisfactory that the available encoding for diplomatic transcription does not make it possible to capture and represent all the variants of a phenomenon, within the same category.

The manuscript encoding in HIW has been revised several times during the project’s ten years of existence. There has been a movement from trying to capture and reflect the “what happened here?” of series of alterations, to, when this task grew too complex and difficult, merely trying to represent, diplomatically and detailed, what was written on the page. The difference between these two approaches mainly being that the former involved analysing alterations, while the latter avoids analysis. We concluded that the best we could do was to represent (transcribe and encode) all individual alterations, as diplomatic as possible, and to hope that we could find a solution which would make it possible for our future users to take on the task of analysing alterations and presenting theories of the text’s genesis. This conclusion stems from several reasons where the two more important are the issue of interpretation and issues concerning encoding.

1. Interpretation:

- Encoders will often interpret revision sequences differently, resulting in different orders and chronologies for the same revision

2. Encoding:

- It’s problematic to encode large alterations because of overlapping hierarchies; e.g. in a drama four pages are deleted; the deletion starts in the middle of a speech and ends in another of the same role’s speeches, removing a part of the dialogue and joining the two halved speeches

- Complex substitutions are also problematic to encode; e.g. a deleted word is replaced with two added words, one of them is then replaced with a new added word, and then another reading is added to replace the first addition, but this is not deleted

I assume that you have all seen these kinds of alterations and that giving more examples is superfluous.

Analysing revision involves interpretation in various degrees. We believe the better way to avoid too much interpretation in the encoding is to leave it relatively simple. The task of analysing is left to others and the results can be added as new (stand off) layers of encoding. This will also allow different interpretations to come forward, thus creating different hypotheses about the genesis of the text. After all we can seldom do more than hypothesize around the genesis of a text, so for builders of textual archives this would seem the better approach.

I think we should discuss how we can develop the existing encoding to include and reflect the genetic perspective, as well as find an encoding solution for transpositions and clarifications. In a discussion entitled “Additions, deletions and structure” 6 on the MS SIG list in October last year, I argued (in my last posting) that <add> and <del> should’ve been defined as inter-level elements, since what semantically constitute additions and deletions – and I add today substitutions and transpositions – vary from single characters and words or phrases within paragraphs, up to several pages of text.

I propose that we rethink <add>, <del> and <subs> and remake them as inter-level elements and that we add an inter-level element for transpositions. With such a revision of the encoding of primary sources, we would achieve a much better basis for analysing the processes of revision and a better and more consistent manuscript encoding.

I have avoided mentioning <addSpan/> and <delSpan/> so far, for although they are what the TEI Guidelines offer for longer added or deleted sequences of text, and even if they can suffice, we still have the problem of large substitutions and transpositions. 7 I think we should acknowledge that the structures of revision in a working draft manuscript is often the most important and interesting feature, and we could acknowledge this by making it possible to encode the revision structures as the primary structure of the text.

Such a revision of the encoding would turn the textual hierarchy of the working draft manuscript upside down, making the structure of revisions the primary encoding level, and the structure of the text’s genre the secondary. In practice this would mean fragmenting the text’s structure instead of the alteration’s structure. A consequence of this is making genetic analysis easier. Thus the perspective guiding the encoding would decide which hierarchy we’d prioritize, just like it does when we encode verse dramas or some other genre containing overlapping hierarchies.

References

- Bryant, John 2002. The Fluid Text. A theory of revision and editing for book and screen, Ann Arbor, The University of Michigan Press.

- TEI Consortium, eds. TEI P5: Guidelines for Electronic Text Encoding and Interchange. Version 1.1.0. 4th of July 2008. TEI Consortium. http://www.tei-c.org/Guidelines/P5/ (7th of September 2008).

- TEI MS SIG list. http://listserv.brown.edu/archives/cgi-bin/wa?A0=TEI-MS-SIG (7th of September 2008).

Facsimiles from Henrik Ibsen’s manuscripts:

Brand (published 1866)

- Collin 262, 4°, I.1.1. The Royal Library of Copenhagen. Copenhagen, Denmark

The Epic Brand (never published by the author)

- NKS 2869, 4°, 1. The Royal Library of Copenhagen. Copenhagen, Denmark

Love’s Comedy (published 1862)

- UBiT Ms Oct. 375. The University Library of Trondheim. Trondheim, Norway

Poems (published 1871)

- NBO Ms.4º 1110a. The National Library of Norway. Oslo, Norway

The Wild Duck (published 1884)

- NBO Ms.8º 952. The National Library of Norway. Oslo, Norway

- NBO Ms.4º 1115a. The National Library of Norway. Oslo, Norway

Footnotes

- 1.

- They can of course also contain more than one version, but their scribes can be said to intend to transfer one version only. Back to context...

- 2.

- The

current HIW DTD definition of <clarification>:

<!ELEMENT clarification %om.RR; (#PCDATA | %m.Incl; | add | corr | del | hi | speaker)* > <!ATTLIST clarification %a.global; resp IDREF %INHERITED; cert CDATA #IMPLIED place CDATA #IMPLIED hand IDREF %INHERITED;>Back to context... - 3.

- TEI Consortium, eds. “11.3.6 Cancellation of Deletions and Other Markings” TEI P5: Guidelines for Electronic Text Encoding and Interchange. Version 1.1.0. 4th of July 2008. TEI Consortium. http://www.tei-c.org/release/doc/teip5doc/en/html/PH.html#PHCD (7th of September 2008) Back to context...

- 4.

- We have created a solution using the <seg>

element for the inline transpositions, but for the larger transpositions, we

haven’t been able to find an adequate solution. We have therefore created a

general element parallel to <seg>, but for use directly in

<div> etc., and called it <blockSeg>. Here is an

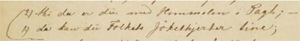

example of the encoding:

<blockSeg type=”transposition_lines” id=”tp_no1”> <lb/><note type=”transposition_lines” resp=”author”>2</note> <l>thi da er du med Himmelen i Pagt; –</l> </blockSeg> <blockSeg type=”transposition_lines” corresp=”tp_no1”> <lb/><note type=”transposition_lines”resp=”author”>1</note> <l>da kan du Folkets Jøkelhjerter tine;</l></blockSeg>

Here’s the DTD definition of <blockSeg>:-

- From The Epic Brand, NKS 2869, 4°, 1. The Royal Library of Copenhagen, Denmark

<!ELEMENT blockSeg %om.RR; (%m.refsys; | add | app | blockSeg | del | castItem | join | l | note | sp | stage | row )* > <!ATTLIST blockSeg %a.global; hand IDREFS #IMPLIED type CDATA #IMPLIED >Much can probably be said about this solution, and I’m not sure whether I still think it’s a good solution, but it made it possible for us to represent the transposition diplomatically, and that was our goal; in that respect at least it’s functional. Back to context... -

- 5.

- TEI MS SIG list, 2008. “<subst> and genetic editions”, initial posting by Elena Pierazzo, http://listserv.brown.edu/archives/cgi-bin/wa?A2=ind0807&L=TEI-MS-SIG&P=R90&D=0 Back to context...

- 6.

- TEI MS SIG list, 2007. “Additions, deletions and structure”, initial posting by Hilde Bøe, http://listserv.brown.edu/archives/cgi-bin/wa?A2=ind0710&L=TEI-MS-SIG&D=0&P=196 Back to context...

- 7.

- I don’t think creating <substSpan> and <transpositionSpan> would do. Back to context...